How women in India reclaimed the protest power of ripped jeans

After an Indian politician recently tried to shame a woman for wearing ripped jeans, women’s responses were swift and sharp.

(Twitter/@prag65043538, @sherryshroff, @ruchikokcha)

Deepali Dewan, University of Toronto

After an Indian politician recently tried to shame a woman for wearing ripped jeans, women’s responses were swift and sharp.

(Twitter/@prag65043538, @sherryshroff, @ruchikokcha)

Deepali Dewan, University of Toronto

A recently-elected Indian chief minister associated with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government sparked a swift and impassioned social media storm after he made a negative comment about a woman wearing ripped jeans on March 17.

While speaking at a workshop organized by the State Commission for Protection of Child Rights, Uttarakhand Chief Minister Tirath Singh Rawat said he was shocked and outraged after he encountered a woman on his flight wearing ripped jeans. The minister took issue with her exposed knees. Rawat also pointed out that the woman was with her children and a leader of an NGO. He said these two facts combined with the ripped jeans put her moral values even further into question. The clip was circulated widely in the Indian press.

Maybe it was the creepy way Chief Minister Rawat described himself scanning the woman’s body with his gaze or the shaming tone he used when he asked her where her husband was. Or perhaps it was the judgemental way he expressed his opinion that ripped jeans were incommensurate with running an NGO and being a mother, and not in line with his version of Indian values. Or it could even have been the casual way he felt he had the right to interrogate her clothing choice at all.

But women across India responded in protest with alacrity and speed as they posted photos of themselves in ripped jeans on social media. Some even cut holes into their jeans before posting the defiant images. At one point, #RippedJeans was top trending on Twitter in India.

As an art historian of South Asian visual culture, I am interested in the ways images convey meaning. Why did ripped jeans cause such a stir? What are the codes contained in this seemingly simple but ubiquitous fashion trend?

Historians and writers such as Ramchandra Guha have acknowledged how serious affronts to civil rights occurring in India today have been steadily eroding India’s democracy. Within these deep and structural challenges, the recent ripped-jeans demonstrations offer a glimmer of hope. The online storm is a sign that India’s democracy is resilient and that protest can emerge in unexpected ways.

Read more:

In India, Modi’s nationalism quashes dissent with help from the media

The meaning of clothing

India has a history of using clothing to convey political meaning and even as a strategy to incite change. As anthropologist Emma Tarlo explains in Clothing Matters: Dress and Identity in India, what one chooses to wear has long been understood as a maker of meaning, a way of both expressing and shaping personal identity.

For example, in 1903 (as I’ve written about elsewhere) the wealthiest man in India at the time, the Nizam of Hyderabad, chose to wear a simple western suit to the 1903 Delhi Durbar, a ceremony marking the coronation of the British monarch. In so doing, he instigated the displeasure of a British colonial administration who liked to see their native rulers dressed as spectacles of South Asian finery.

Later, Mohandas K. Gandhi wore a dhoti to have tea at Buckingham Palace in 1931. The dhoti, made out of hand-spun cotton, was part of the larger khadi movement to protest the import of cheaper-than-local machine-made British products that led to the decline of the Indian textile industry.

Mohandas K. Gandhi in England, 1931.

(James Mills Collection/AP)

Mohandas K. Gandhi in England, 1931.

(James Mills Collection/AP)

Jeans go global

In Global Denim, scholars explore the different contexts of jean wearing around the world. Jeans in India have a specific history and context — and the meaning of a pair of jeans has evolved since the 1970s when they were first popularly introduced.

Jeans have humble beginnings. They were developed as a durable attire for mine workers in the United States in the 1930s, but grew in popularity through association with cowboy films. In 1955, James Dean secured the jean’s association with youth culture, rebellion and counterculture when he wore them in Rebel Without A Cause to arousing effect. By the 1970s, this popularity had expanded. Punk and grunge bands put gaping holes in jeans to convey anger toward convention and society’s obsession with material things.

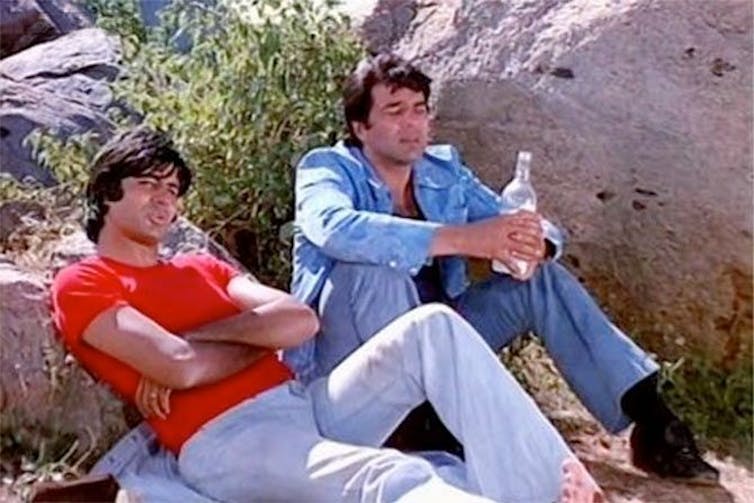

A movie still from ‘Sholay,’ 1975.

(Sippy Films)

A movie still from ‘Sholay,’ 1975.

(Sippy Films)

As a kid, whose family had migrated from India to the U.S. in the mid 1970s, I recall being a wide-eyed ‘80s teenager in a New York City store. The shop carried two floors of nothing but ripped jeans. I was shocked that the store had been able to source so many second-hand jeans. Only later, did I understand that clothing manufacturers had started producing new jeans with holes in them as part of their product line. In this way, they had turned dissent into a marketable fashion statement.

In India, the jean was popularized in the post-independence period with exposure to western films. The clamour for jeans received a huge boost when irresistible bad boy film star Amitabh Bachchan wore jeans in the 1975 mega-blockbuster, Sholay. The jeans were a reflection of the youthful and rebellious nature of his character.

But jeans were still inaccessible to the majority of India’s youth. India’s self-sufficient economic policies made access to foreign brands difficult or very expensive. Indians eventually turned to tailors to stitch their jeans. Finally, by the '90s there were domestic brands of jeans to be had, although foreign brands still had cachet, especially in urban areas.

After India’s economic liberalization in the 1990s, foreign brands became more available, albeit still expensive. Ripped jeans came soon after with the increased exposure to international trends.

So in India, jeans were associated with the West, modernity and youth culture. That is to an extent still true. But jeans with holes have the added association with protest and dissent.

Protest power

Chief Minister Rawat has since apologized. But the backlash to his comments seems to be as much about his and his party’s policing of women’s bodies as about their policing of free speech, which ripped jeans have come to symbolize in general.

Today, shopping for my 14-year-old daughter in Toronto, it is hard to find anything but ripped jeans. In fact, ripped jeans are so mainstream that in some sense their association with rebellion and dissent has been muted by the process of commodification.

This is a market that even BJP allies have invested in. One company, owned by a yoga guru that sells ripped jeans tweeted: “Our jeans are ripped, but we haven’t ripped them so much also so as to lose our Indian-ness and our values.”

Ironically, Chief Minister Rawat’s comments, which sound out of touch not only for their arcane notions of modesty but also the agency they ascribe to ripped jeans, have infused new vigour into an old symbol. At least for a moment in India, it seems, ripped jeans have reclaimed their protest power.

This is a corrected version of story originally published on March 25, 2021. It was James Dean who starred in 'Rebel Without a Cause,’ not Marlon Brando.

Deepali Dewan, Dan Mishra Curator of South Asian Art & Culture, Royal Ontario Museum / Associate Professor, Department of Art History, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.