Sure, video games want to get you hooked on spending. But there's no evidence they can manipulate you

YouTube/Screenshot

Ben Egliston, Queensland University of Technology; Jane Mavoa, The University of Melbourne, and Marcus Carter, University of Sydney

YouTube/Screenshot

Ben Egliston, Queensland University of Technology; Jane Mavoa, The University of Melbourne, and Marcus Carter, University of Sydney

The ABC’s latest Four Corners report is an investigation into how videogames are “deliberately designed to get people hooked”.

It describes the use of gambling-like “loot boxes” in games, the hotly debated notion of videogame addiction and, to a lesser extent, the “predatory techniques” of using user data and AI to increase spending in freemium games (free to play games which are monetised through in-app transactions and advertising).

The process of monetising and collecting data through videogames does require scrutiny, as it can be problematic for some users. But in working out what the harms are, we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact videogames are enjoyable and valuable for the vast majority.

The Four Corner’s program asks, ‘are you being played?’

via ABC 4 Corners program

The Four Corner’s program asks, ‘are you being played?’

via ABC 4 Corners program

How do game companies use data?

Videogame production is increasingly supported by collecting large amounts of player data. Game developers use this data to optimise game design and, perhaps more commonly, how games are monetised.

Historically, data about players’ actions and gaming experiences have been collected through quality assurance testing, or by game developers trawling through online forums. This has changed with the rise of data mining and analysis, referred to as telemetry, or more commonly as “data analytics”.

Such approaches were once limited to large “Triple A” companies such as EA or social gaming giants like Zynga. Only the biggest game designers could afford in-house software engineers to create these systems, and data analysts to use them.

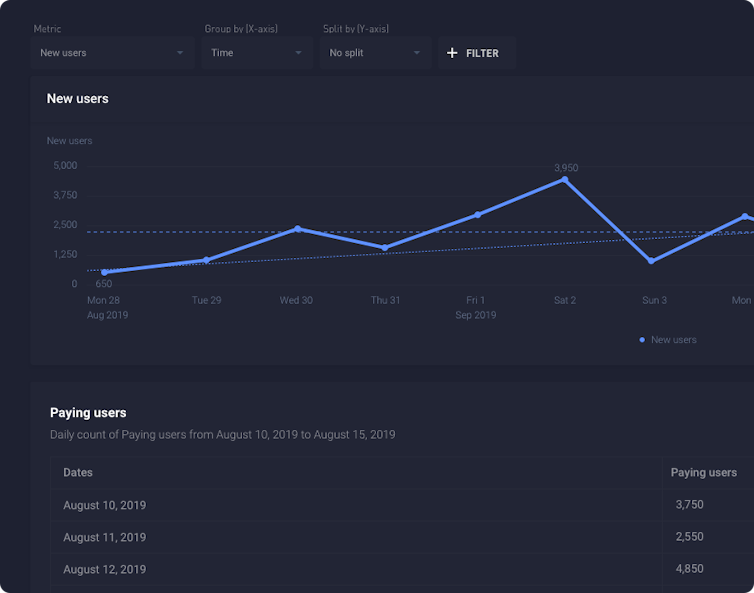

Today data analytics are relatively cheap, accessible tools aimed at both big and small independent developers. Data analytics suites are a core feature of game development software, are offered by tech giants such as Amazon and are also sold by standalone analytics providers such as GameAnalytics.

Analytics might involve simple data such as the number of downloads, or may provide more complex insights, such as in-game behaviour, playing time and frequency of play.

The shift to freemium play, encouraged by smartphone platforms, has made it particularly important to collect data on in-app purchasing. This could include players’ geographic location, their device and operating system and their spending habits.

In turn, this can help game developers to determine which players are more likely to spend money while playing, and how to optimise the placement of in-game ads — a major source of revenue in freemium games.

GameAnalytics interface tracking a game’s new users over time.

GameAnalytics

GameAnalytics interface tracking a game’s new users over time.

GameAnalytics

The software Game of Whales —

named after the industry’s practice of calling big spenders “whales” —

claims to use AI to track players’ behaviour in real-time and interact with them in a way that maximises “lifetime value”, which is the total amount of revenue a player will generate while playing a game.

These tools are framed as allowing both large and smaller developers to create conditions which increase player spending. For example, they might minimise ads and encourage increased playing time for a high-value “whale”, while providing more ads for users who are unlikely to make in-app purchases.

This is the subset of the gaming industry that frames itself as being able to “control” players through data analytics.

What’s the data on the data?

However, while analytics companies would suggest their products work as promised, we lack scholarly evidence that data capture allows videogame companies to control our minds or our wallets.

As critics of Harvard Professor Shoshana Zuboff’s surveillance capitalism theory would argue, just because game companies collect our data, that doesn’t mean they can automatically control how we behave. Data does not rob us of our agency, writes Virginia Tech’s Lee Vinsel:

[…] it seems that Mark Zuckerberg can’t sell me fucking socks, let alone purposefully/significantly change my politics or self-concept.

Research on how developers use data analytics reflects this ambivalence. One study of French videogame company Ubisoft, and its use of data, suggests data collection “augments” (or enhances) products, rather than necessarily manipulating users into continued spending via microtransactions.

Read more:

Facebook's virtual reality push is about data, not gaming

Are you being manipulated?

The recent Four Corners report frames the gaming industry as a largely manipulative one. It attacks the industry’s calculated pricing strategies, which can affect how we value in-game purchases.

But these same strategies are also widely used in the restaurant industry. Even supermarkets are designed so customers spend as much time as possible inside.

Push notifications that encourage play and consumption have a real-world equivalent, too, such as scent machines at Disneyland used to boost cotton candy and caramel apple sales.

Yet, we don’t think of these subtle techniques as completely robbing us of our agency. So why does the gaming industry draw so much criticism?

Are there solutions?

Many of the mobile and freemium games discussed in the Four Corners report are designed for children who do need greater protection since, according to some psychologists, they don’t “comprehend commercial messages in the same way as more mature audiences”.

In part, concerns about spending in games can be attributed to parents and non-players misunderstanding how virtual goods can actually have real value for players.

A virtual outfit can still help someone express their identity. A helpful strategy could be for parents to discuss with their kids what it means to spend real money on virtual goods and why they want to.

Although, the way some games target whales to encourage unlimited spending is a source of genuine concern. When it comes to monetising responsibly, game platforms and developers both have a role to play.

The solution may be to introduce spending limits, which research has found helps gamblers avoid problem gambling.

Looking after children

It’s important not to conflate issues with how game companies encourage in-game spending with gaming addiction, about which there is significant disagreement among scholars.

Speaking to the Four Corners team, one psychiatrist frames gameplay through language such as “detox” and “relapse”. This approach, which critics refer to as a form of “concept creep”, can result in children’s play being unnecessarily pathologised.

Read more:

Gaming addiction as a mental disorder: it's premature to pathologise players

In our research, we found reason to be concerned by how this type of discourse can negatively affect children with healthy digital play habits, by stigmatising their play, causing parent-child conflict and devaluing concern about drug and alcohol addiction.

Children have the right to play and this extends to the digital world.

Ben Egliston, Postdoctoral research fellow, Digital Media Research Centre, Queensland University of Technology; Jane Mavoa, PhD candidate researching children's play in digital games, The University of Melbourne, and Marcus Carter, Senior Lecturer in Digital Cultures, SOAR Fellow., University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.