How safe are your data when you book a COVID vaccine?

Shutterstock

Joan Henderson, University of Sydney and Kerin Robinson, La Trobe University

Shutterstock

Joan Henderson, University of Sydney and Kerin Robinson, La Trobe University

The Australian government has appointed the commercial company HealthEngine to establish a national booking system for COVID-19 vaccinations.

Selected through a Department of Health limited select tender process, the platform is being used by vaccine providers who don’t have their own booking system.

However, HealthEngine has a track record of mishandling confidential patient information.

Previous problems

In 2019 the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission took HealthEngine to court for allegedly skewing reviews and ratings of medical practices on its platform and selling more than 135,000 patients’ details to private health insurance brokers.

The Federal Court fined HealthEngine A$2.9 million in August 2020, just eight months ago.

Department of Health associate secretary Caroline Edwards told a Senate hearing the issues were “historical in nature, weren’t intentional and did not involve the sharing of clinical or medical related information”.

How might the alleged misconduct, which earned HealthEngine A$1.8 million, be considered “historical in nature” and “not intentional”?

Edwards added that HealthEngine had strengthened its privacy and security processes, following recommendations in the ACCC’s digital platforms inquiry report. Regarding the new contract, she said:

[…] the data available to HealthEngine through what it’s been contracted to do does not include any clinical information or any personal information over what’s required for people to book.

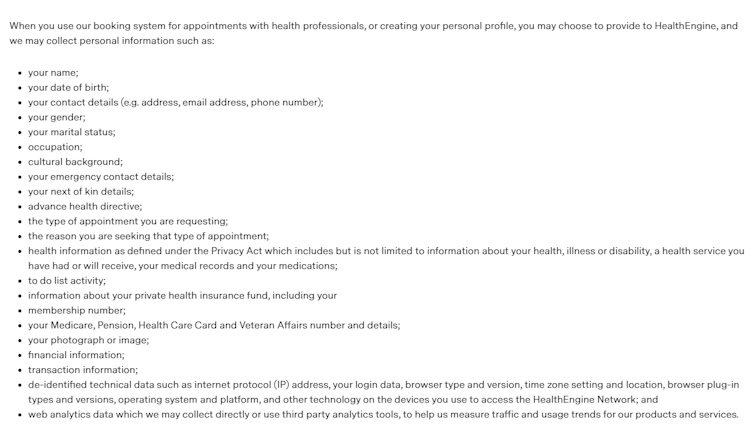

That’s somewhat reassuring, considering the larger amount of information usually requested from patients booking an appointment (as per HealthEngine’s current Privacy Policy).

The list of personal information HealthEngine may collect from patients booking an appointment with a health professional.

Screenshot

The list of personal information HealthEngine may collect from patients booking an appointment with a health professional.

Screenshot

Importantly, HealthEngine then owns this information. This raises an important question: why is so much personal information requested just to book an ordinary appointment?

A need for accessible information

While using HealthEngine to book a vaccination is not mandatory, individual practices will determine whether patients can make appointments over the phone, are directed to use HealthEngine’s platform, or another existing platform.

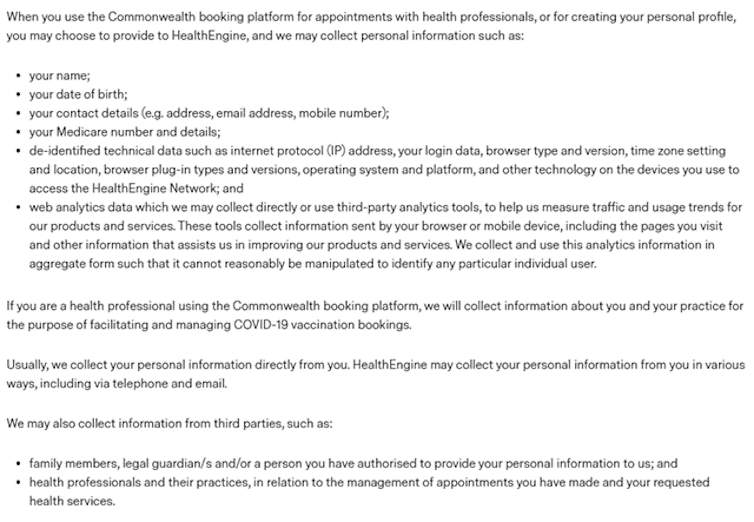

Personal details currently requested through HealthEngine’s vaccination booking system are:

HealthEngine’s Privacy Policy for COVID-19 vaccination bookings.

screenshot

HealthEngine’s Privacy Policy for COVID-19 vaccination bookings.

screenshot

This list is substantially shorter than the one concerning non-COVID related bookings. That said, there’s still more information being gathered than would be required for the sole purpose of arranging a patient’s vaccination.

What is the justification for this system to collect data about patients’ non-COVID medical and health services, or the pages they visit?

A representative from the Department of Health told The Conversation that all patient data collected through the COVID vaccination booking system was owned by the department, not HealthEngine. But what need would the department have to collect web analytics data about what sites a patient visits?

An underlying administrative principle of any medical appointment platform is that it should collect the minimum amount of data needed to fulfil its purpose.

Also, HealthEngine’s website reveals the company has, appropriately, created an additional privacy policy for its COVID-19 vaccination booking platform. However, this is currently embedded within its pre-existing policy. Therefore it’s unlikely many people will find, let alone read it.

For transparency, the policy should be easy to find, clearly labelled and presented as distinct from HealthEngine’s regular policies. A standalone page would be feasible, given the value of the contract is more than A$3.8 million.

What protections are in place?

Since the pandemic began, concerns have been raised regarding the lack of clear information and data privacy protection afforded to patients by commercial organisations.

Luckily, there are safeguards in place to regulate how patient data are handled. The privacy of data generated through health-care provision (such as in general practices, hospitals, community health centres and pharmacies) is protected under state and territory or Commonwealth laws.

Data reported (on a compulsory basis) by vaccinating clinicians to the Australian Immunisation Register fall within the confines of the Australian Immunisation Register Act 2015 and its February 2021 amendment.

Read more:

Queensland Health's history of software mishaps is proof of how hard e-health can be

Also, data collected through the Department of Health’s vaccination registration system are legally protected under the Privacy Act 1988, as are data collected via HealthEngine’s government-approved COVID-19 vaccination booking system.

But there’s still a lack of clarity regarding what patients are being asked to consent to, the amount of information collected and how it’s handled. It’s a critical legal and ethical requirement patients have the right to consent to the use of their personal information.

If the privacy policy of a booking system is unclear, this presents risk for patients who have challenges with the English language, literacy, or are potentially distracted by pain or anxiety while making an appointment.

Shutterstock

If the privacy policy of a booking system is unclear, this presents risk for patients who have challenges with the English language, literacy, or are potentially distracted by pain or anxiety while making an appointment.

Shutterstock

Gaps in our knowledge

As health information managers, we had further questions regarding the government’s decision to appoint HealthEngine as a national COVID-19 vaccination booking provider. The Conversation put these questions to HealthEngine, which forwarded them to the Department of Health. They were as follows.

Is there justification for the rushed outsourcing of the national appointment platform, given the number of vaccine recipients whose data will be collected?

How did the department’s “limited select tender” process ensure equity?

Who will own data collected via HealthEngine’s optional national booking system?

What rights will the “owner” of the data have to give third-party access via the sharing or selling of data?

What information will vaccine recipients be given on their right to not use HealthEngine’s COVID-19 vaccination booking system (or any appointment booking system) if they’re uncomfortable providing personal information to a commercial entity?

How will these individuals be reassured they may still receive a vaccine, should they not wish to use the system?

In response, a department representative provided information already available online here, here, here and here. They gave no clarification about how patients might be guided if they’re directed to the HealthEngine platform but don’t want to use it.

They advised the data collected by HealthEngine:

can not be used for secondary purposes, and can only be disclosed to third-party entities as described in HealthEngine’s tailored Privacy Policy and Collection Notice, as well as the department’s Privacy Notice.

But according to HealthEngine’s privacy policy, this means patient data could still be provided to other health professionals a patient selects, and de-identified information given to the Department of Health. The policy states HealthEngine may also disclose patients’ personal information to:

third-party IT and software providers such as Adobe Analytics

professional advisers such as lawyers and auditors, for the purpose of providing goods or services to HealthEngine

courts, tribunals and law enforcement, as required by law or to defend HealthEngine’s legal rights and

others parties, as consented to by the patient, or as required by law.

Ideally, the answers to our questions would have helped shed light on the extent to which patient privacy was considered in the government’s decision. But inconsistencies between what is presented in the privacy policies and the Department of Health’s response have not clarified this.

Read more:

The government is hyping digitalised services, but not addressing a history of e-government fails

Joan Henderson, Senior Research Fellow (Hon). Editor, Health Information Management Journal (HIMJ), University of Sydney and Kerin Robinson, Adjunct Associate Professor, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.