Apple's new 'app tracking transparency' has angered Facebook. How does it work, what's all the fuss about, and should you use it?

Amr Alfiky/AP

Paul Haskell-Dowland, Edith Cowan University and Nikolai Hampton, Edith Cowan University

Amr Alfiky/AP

Paul Haskell-Dowland, Edith Cowan University and Nikolai Hampton, Edith Cowan University

Apple users across the globe are adopting the latest operating system update, called iOS 14.5, featuring the now-obligatory new batch of emojis.

But there’s another change that’s arguably less fun but much more significant for many users: the introduction of “app tracking transparency”.

This feature promises to usher in a new era of user-oriented privacy, and not everyone is happy — most notably Facebook, which relies on tracking web users’ browsing habits to sell targeted advertising. Some commentators have described it as the beginnings of a new privacy feud between the two tech behemoths.

So, what is app tracking transparency?

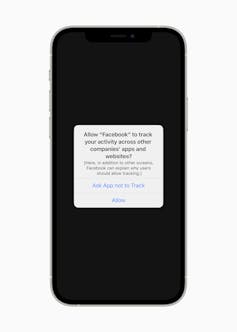

App tracking transparency is a continuation of Apple’s push to be recognised as the platform of privacy. The new feature allows apps to display a pop-up notification that explains what data the app wants to collect, and what it proposes to do with it.

Privacy | App Tracking Transparency | Apple.

There is nothing users need to do to gain access to the new feature, other than install the latest iOS update, which happens automatically on most devices. Once upgraded, apps that use tracking functions will display a request to opt in or out of this functionality.

A new App Tracking Transparency feature across iOS, iPadOS, and tvOS will require apps to get the user’s permission before tracking their data across apps or websites owned by other companies.

Apple newsroom

A new App Tracking Transparency feature across iOS, iPadOS, and tvOS will require apps to get the user’s permission before tracking their data across apps or websites owned by other companies.

Apple newsroom

How does it work?

As Apple has explained, the app tracking transparency feature is a new “application programming interface”, or API — a suite of programming commands used by developers to interact with the operating system.

The API gives software developers a few pre-canned functions that allow them to do things like “request tracking authorisation” or use the tracking manager to “check the authorisation status” of individual apps.

In more straightforward terms, this gives app developers a uniform way of requesting these tracking permissions from the device user. It also means the operating system has a centralised location for storing and checking what permissions have been granted to which apps.

What is missing from the fine print is that there is no physical mechanism to prevent the tracking of a user. The app tracking transparency framework is merely a pop-up box.

It is also interesting to note the specific wording of the pop-up: “ask app not to track”. If the application is using legitimate “device advertising identifiers”, answering no will result in this identifier being set to zero. This will reduce the tracking capabilities of apps that honour Apple’s tracking policies.

However, if an app is really determined to track you, there are many techniques that could allow them to make surreptitious user-specific identifiers, which may be difficult for Apple to detect or prevent.

For example, while an app might not use Apple’s “device advertising identifier”, it would be easy for the app to generate a little bit of “random data”. This data could then be passed between sites under the guise of normal operations such as retrieving an image with the data embedded in the filename. While this would contravene Apple’s developer rules, detecting this type of secret data could be very difficult.

Read more:

Your smartphone apps are tracking your every move – 4 essential reads

Apple seems prepared to crack down hard on developers who don’t play by the rules. The most recent additions to Apple’s App Store guidelines explicitly tells developers:

You must receive explicit permission from users via the App Tracking Transparency APIs to track their activity.

It’s unlikely major app developers will want to fall foul of this policy — a ban from the App Store would be costly. But it’s hard to imagine Apple sanctioning a really big player like Facebook or TikTok without some serious behind-the-scenes negotiation.

Why is Facebook objecting?

Facebook is fuelled by web users’ data. Inevitably, anything that gets in the way of its gargantuan revenue-generating network is seen as a threat. In 2020, Facebook’s revenue from advertising exceeded US$84 billion – a 21% rise on 2019.

The issues are deep-rooted and reflect the two tech giants’ very different business models. Apple’s business model is the sale of laptops, computers, phones and watches – with a significant proportion of its income derived from the vast ecosystem of apps and in-app purchases used on these devices. Apple’s app revenue was reported at US$64 billion in 2020.

With a vested interest in ensuring its customers are loyal and happy with its devices, Apple is well positioned to deliver privacy without harming profits.

Should I use it?

Ultimately, it is a choice for the consumer. Many apps and services are offered ostensibly for free to users. App developers often cover their costs through subscription models, in-app purchases or in-app advertising. If enough users decide to embrace privacy controls, developers will either change their funding model (perhaps moving to paid apps) or attempt to find other ways to track users to maintain advertising-derived revenue.

If you don’t want your data to be collected (and potentially sold to unnamed third parties), this feature offers one way to restrict the amount of your data that is trafficked in this way.

But it’s also important to note that tracking of users and devices is a valuable tool for advertising optimisation by building a comprehensive picture of each individual. This increases the relevance of each advert while also reducing advertising costs (by only targeting users who are likely to be interested). Users also arguably benefit, as they see more (relevant) adverts that are contextualised for their interests.

It may slow down the rate at which we receive personalised ads in apps and websites, but this change won’t be an end to intrusive digital advertising. In essence, this is the price we pay for “free” access to these services.

Read more:

Facebook data breach: what happened and why it's hard to know if your data was leaked

Paul Haskell-Dowland, Associate Dean (Computing and Security), Edith Cowan University and Nikolai Hampton, School of Science, Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.