COVID-19 is prompting more people to head to trusted mainstream news sites for information - new research

Need to know: people have been more willing to pay for high-quality information during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2p2play/Shutterstock

Nic Newman, University of Oxford

Need to know: people have been more willing to pay for high-quality information during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2p2play/Shutterstock

Nic Newman, University of Oxford

More than a year after it began, the pandemic continues to cast a dark cloud over both public health and the economy. The news industry is no exception. Across the world, long-established news titles are being closed, and journalists are being laid off, as advertisers take fright in the face of a global economic downturn.

And yet, in this year’s digital news report from the Reuters Institute at Oxford University, my colleagues and I provide evidence that some news brands have benefited from a desire for reliable information around the pandemic - in terms of higher reach, higher trust and more paying subscribers.

It is important to note that our previous survey captured a moment in time before the pandemic - January 2020 - and, a year later, we captured another, when the impact of coronavirus still varied considerably across countries.

In the intervening time we know that most news brands reported at various times, vastly increased usage. Television news, in particular, achieved its biggest audience numbers for years, especially during the first months of the crisis.

Read more:

Coronavirus: people turn to their local news sites in record numbers during pandemic

But our data suggests that consumption now has reverted to a more normal pattern with interest in the news, in most countries, no higher than a year ago.

Trusted brands have done better online

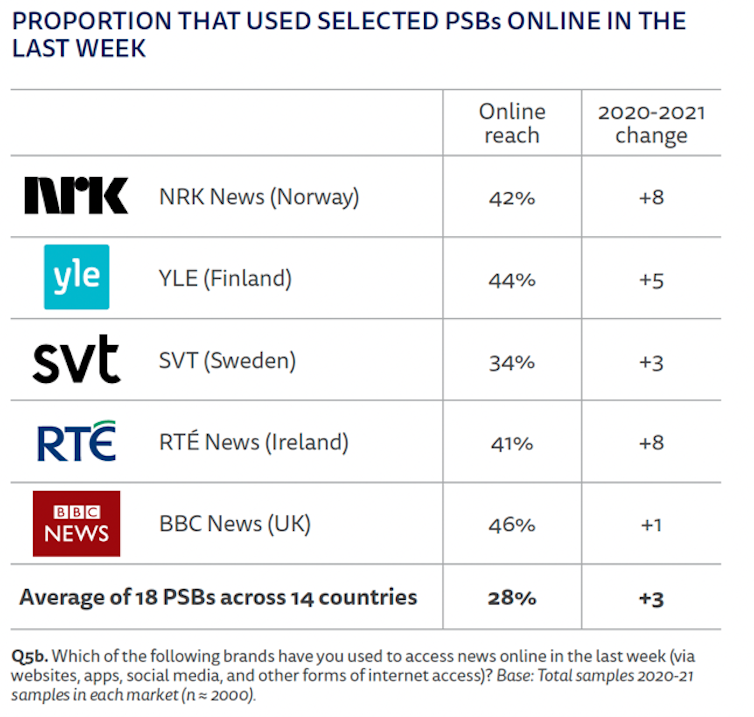

In northern and western Europe, some commercial and public service news sites (those that operate with public funding and as a not-for-profit) continue to attract larger online audiences than they did a year before – and these tend to be those with a higher level of trust. In Norway, VG (Verdens Gang) gained nine percentage point increase in weekly use on 2020, n-tv in Germany gained four, while MTV News in Finland was up by seven points on the year before. Public service media websites have also performed particularly well, perhaps because they have been able to use their reach via TV and radio to promote more detail online.

Rising trust in public sector news audiences.

Nic Newman/RISJ, Author provided

Rising trust in public sector news audiences.

Nic Newman/RISJ, Author provided

The coronavirus story seems to have played to the strengths of public media’s fact-based and specialised coverage, with online coverage including extensive breakdowns of coronavirus data, daily COVID-19 newsletters, and explanatory podcasts.

This has given a boost to a sector whose legitimacy and funding have been threatened by a combination of changing consumer behaviour and reduced funding.

Trust in news up significantly

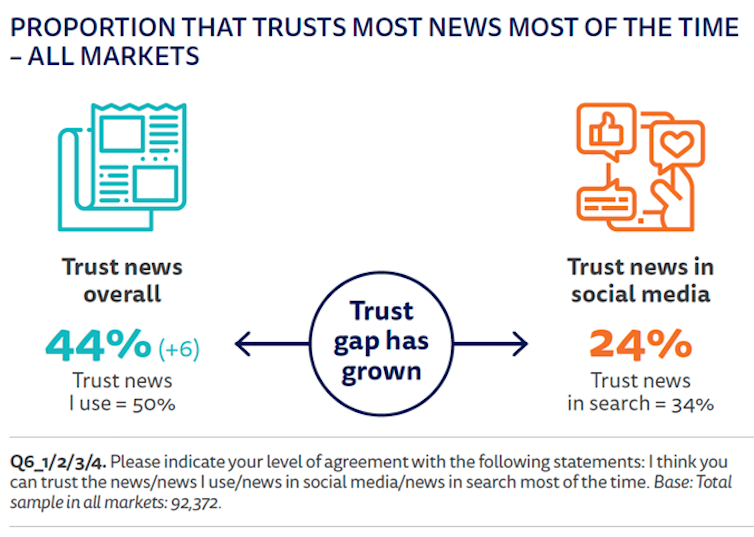

More widely it seems that the crisis has restored some confidence in the news media, after a period which has seen attacks by populist politicians, and the rise of unreliable information often distributed via social media. Trust in the news (44%) is up six percentage points on average and considerably more than that in some countries.

We also find a growing trust gap between the news sources people generally rely on and the news they find in social media and search, which has remained unchanged on a like-for-like basis. This may be because coronavirus has made the news seem more straightforward and fact-based, at the same time as squeezing out more partisan political news in some countries.

The US is clearly an exception, following deep divisions over a disputed election and widespread protests against racial inequality. The US, Mexico and Turkey are the only countries not to have seen an increase in trust this year.

Trust in news: new research.

Nic Newman/RISJ, Author provided

Trust in news: new research.

Nic Newman/RISJ, Author provided

None of this provides any cause for complacency. These gains only partially reverse falls in trust in the news over the last few years and concern about false and misleading information remains higher than ever. The majority of our global sample (58%) said that had seen false or misleading misinformation about COVID-19 or other health issues in the last week – higher in parts of Africa and Latin America.

With lives at stake, the pandemic has also caused search and social media platforms to take a much tougher approach to taking down damaging and harmful content. They have also showcased reliable sources of information about COVID-19 – including official statistics and well trusted news brands. This greater premium on trusted sources in online environments is likely to continue long after COVID-19 has retreated.

Launch of the Reuters Institute digital news report 2021.

For many publishers, COVID-19 has also accelerated plans to get readers to pay for content online – via subscription or donation models. El Pais in Spain, El Tiempo in Colombia and News 24 in South Africa are among those to have started their paywall journeys during the pandemic.

But with more content going behind paywalls, the pandemic has also raised fears about information inequality. In any future health crisis, will those who can afford it get better quality information than those who can’t?

Digital habits are changing

During this crisis, many older people have embraced new digital platforms for the first time, enjoying the convenience of shopping online and video conferencing. Subscription services of all types have boomed – especially entertainment streaming services such as Netflix. News may be able to ride on the back of this trend, but as household budgets tighten news organisations may also struggle to keep customers, let alone win new ones.

Our data also shows that people have relied even more on the smartphone for communicating with friends but also for accessing news (73% average weekly use). This shift, which has been under way for some time, nevertheless has major implications for the formats of news. Beautifully presented visual updates and short videos have all performed well during the crisis, as have mobile-first social networks like TikTok and Instagram – used both to distract and entertain.

Year after year, our survey has documented the shift towards more digital, social, and mobile consumption – slowly chipping away at the business models as well as the confidence of many media companies. Now the shock of COVID-19 combined with accelerating technological change is forcing a more fundamental rethink about how journalism should operate in the next decade, as a business, in terms of technology, but also as a profession.

Nic Newman, Senior Research Associate, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.